Across Nigeria, the rising cost of baby food has become an unbearable burden for nursing mothers. What was once a manageable part of household expenses has now turned into a source of distress, forcing many mothers to seek cheaper, homemade alternatives. From Lagos to Kano and Port Harcourt, countless women are grinding local cereals and grains to prepare meals for their infants as the prices of imported baby foods skyrocket beyond the reach of average families.

The growing trend highlights the deeper impact of inflation and economic hardship on families, particularly women and children who are most affected by the soaring prices of essential goods.

Mothers Turn to Local Solutions as Imported Baby Foods Become Luxury Items

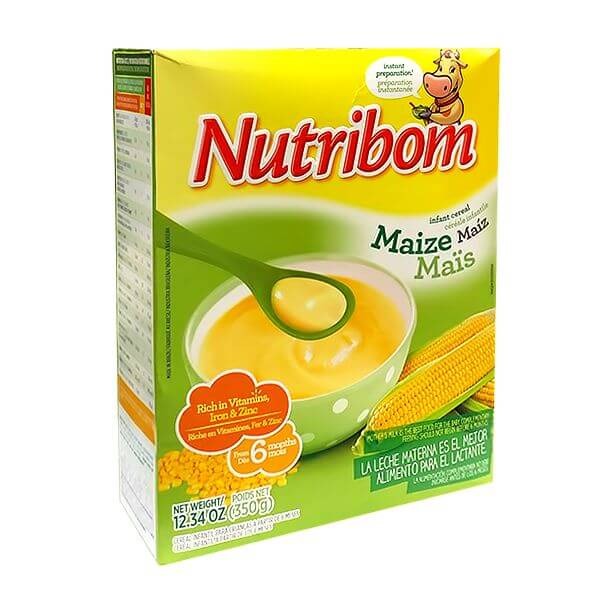

For decades, imported baby foods such as Cerelac, SMA Gold, NAN, and Nutrend have been trusted household names. However, the economic reality of 2025 has made these products unaffordable to many. A single tin of baby cereal now sells between ₦20,000 and ₦50,000, depending on the brand and size — a sharp rise from the ₦6,000 to ₦9,000 range recorded just a year ago.

In response, many mothers are turning to locally made substitutes like blended rice powder, guinea corn, millet, soya beans, and ground crayfish mixtures to feed their babies. For some, this approach is both nostalgic and practical — a return to traditional feeding methods once used before the dominance of foreign brands.

“Things are just too expensive now. I can’t afford to buy those imported baby foods anymore,” lamented one mother in Lagos. “I have started grinding my own cereals again, just like my mother did when we were young.”

Economic Pressure: The Struggle of the Nigerian Mother

The struggle of nursing mothers reflects the broader picture of Nigeria’s worsening cost of living crisis. Inflation has affected virtually every aspect of life — from housing to food, transportation, and healthcare. For many families, baby formula is now seen as a luxury item rather than a necessity.

New mothers face tough choices between maintaining a balanced diet for their babies and managing other pressing family expenses. Even those who depend on exclusive breastfeeding find it difficult to sustain the practice due to demanding work schedules, inadequate maternity leave, and poor nutritional intake.

Some mothers have been forced to improvise by preparing local cereal mixes at home. Common recipes now include a combination of millet, maize, soybeans, groundnuts, and dried fish, which are roasted, blended, and mixed with milk or palm oil to create nutritious meals for infants.

The Return to Traditional Feeding Methods

Before the widespread use of imported baby formulas, most Nigerian mothers relied on traditional foods for infant nourishment. These local meals were nutrient-dense, affordable, and widely accessible. Now, as economic challenges persist, that tradition is making a strong comeback.

Mothers in both urban and rural areas are rediscovering recipes passed down from older generations. Local cereal blends like “Tom Brown,” “Pap,” “Ogi,” and “Acha Porridge” have regained popularity. Apart from being cost-effective, these meals are often tailored to local taste preferences and provide adequate nutrition when properly prepared.

Nutritionists note that while locally made baby foods can be beneficial, they must be prepared under hygienic conditions to ensure safety and nutritional adequacy. Proper storage, use of clean water, and balanced mixing of grains and protein sources are essential to avoid malnutrition or infections.

Nutrition and Health Concerns: Experts Weigh In

Health experts have expressed both optimism and caution over the growing trend. They acknowledge that homemade baby meals, when done right, can offer comparable nutritional value to commercial brands. However, they warn that improper preparation could expose infants to health risks.

A nutritionist in Abuja noted that parents must be properly educated on how to process and combine local ingredients to achieve balanced nutrition. “Homemade cereals can be excellent substitutes if mothers understand the right proportions of carbohydrates, protein, and micronutrients,” she said. “However, care must be taken to ensure food safety and hygiene.”

Pediatricians also recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life, in line with global health standards, before introducing complementary local foods. But for mothers who face difficulties with breastfeeding, affordable local alternatives remain a practical option amidst harsh economic conditions.

The Role of Government and Policy Gaps

Many Nigerians believe that government intervention is urgently needed to address the inflation crisis affecting essential commodities like baby food. Local production of affordable, high-quality baby cereals could help reduce dependency on imported brands and stabilize prices.

Experts argue that investment in local agriculture, improved processing facilities, and support for small-scale food producers could make a significant difference. Subsidizing infant food production and strengthening food safety regulations would also ensure that local alternatives meet nutritional standards.

Without such policies, mothers will continue to bear the brunt of economic hardship while struggling to provide nutritious meals for their children.

Comparative Analysis: Imported vs Local Baby Foods

| Category | Imported Baby Foods | Locally Made Cereal Mixes |

|---|---|---|

| Average Price (2025) | ₦20,000 – ₦50,000 per tin | ₦3,000 – ₦5,000 per month (homemade) |

| Main Ingredients | Processed grains, milk, synthetic vitamins | Millet, maize, soybeans, groundnuts, fish powder |

| Nutritional Value | Balanced and fortified | Variable, depends on preparation |

| Shelf Life | Long (6–12 months) | Short (1–2 weeks) |

| Accessibility | Urban centers only | Easily available nationwide |

| Main Challenge | High cost, import dependency | Food hygiene, consistency |

Voices of Nigerian Mothers: Real Struggles, Real Choices

Interviews conducted by Vanguard revealed emotional testimonies from mothers who shared their frustrations.

One nursing mother in Abuja stated:

“A tin of my baby’s regular formula now costs over ₦30,000. I earn ₦80,000 monthly, and after paying rent and transport, there’s almost nothing left. Grinding local cereals is the only way I can feed my baby.”

Another mother in Kano said:

“I make a mixture of millet, soya beans, and crayfish for my child. It’s natural and cheaper, though I have to take extra care to keep it clean.”

These personal accounts reflect the determination and creativity of Nigerian women in navigating economic hardship while prioritizing their children’s health.

Conclusion: The Resilience of Nigerian Mothers Amid Economic Hardship

The rising cost of baby food in Nigeria tells a larger story about economic inequality, inflation, and resilience. As mothers return to local feeding methods, it is a reminder of how necessity drives innovation in difficult times.

While the trend highlights adaptability, it also underscores the urgent need for policy interventions to reduce food inflation, support local baby food production, and improve maternal welfare.

In the face of hardship, Nigerian mothers continue to show strength, resourcefulness, and unwavering commitment to their children’s well-being — proving once again that even in tough times, a mother’s love finds a way.